The Internal Model Problem

How motor learning theory can explain Mitchell Robinson's free throw struggles

I've leaned on a strong mathematical, research-based, and problem-solving background for most of my personal life. With my interest and love of sports, I wanted to apply that foundation to explore one of basketball's most puzzling phenomena: why some elite athletes can't make free throws. We know the baseline factors, physical constraints like hand size, strength, and coordination all matter. But there's another dimension that's often overlooked: how the brain learns motor skills through practice, and whether traditional training methods build the neural pathways needed for consistent shooting. In this piece, I'm using New York Knicks center Mitchell Robinson and his free throw struggles as a case study to explore what motor control theory and neuroscience research can tell us about shooting improvement.

When you watch Robinson at the free throw line, a career 51% shooter, it's tempting to chalk it up to “he just can't shoot” or “it's mental.” But neuroscience and motor control theory offer a more precise explanation. The difference between a shooter like Robinson and someone like Steph Curry (91% career) isn't just repetition, it's what happens in the brain during those repetitions, and how the nervous system builds what researchers call an internal model of the shooting motion.1

Feedback vs. Feedforward: How Your Brain Shoots

Picture this: You’re at the free throw line for the very first time in your life. You take a deep breath, bend your knees, and let it fly. The ball clanks hard off the front rim. Your brain immediately registers the error: “Too short. Need more power.” Next attempt, you shoot with the power you believe necessary. This time the ball sails long, hitting the back iron. “Too much. Less power.” You’re caught in a loop, shoot, miss, adjust, and repeat.

Introducing, feedback control, it’s how beginners learn any motor skill. Your brain is essentially playing a game of hot-and-cold, using the outcome of each attempt to adjust the next one. It’s reactive, slow and requires constant thought. Every shot is a new calculation based on a previous outcome.

Now imagine Steph Curry at the line. Before the ball even leaves his fingertips, his brain has already solved the equation. Release angle, launch velocity, release point, and backspin. His motor system executes this program with machine-like precision, and 9 times out of 10, it’s nothing but net. Curry isn’t reacting to errors, in-fact he’s barely thinking at all. His brain has built what neuroscientists call an internal model, a predictive simulation of the entire shooting motion and its outcome.

This is feedforward control, and it’s the hallmark of expertise.2 The brain doesn’t wait for feedback from the environment (did the ball go in?). Instead, it predicts the result before movement even begins and executes a programmed solution. The entire shooting motion has been chunked into a single command.

The difference between these two modes isn’t only about practice time. It’s about what happens in the brain during thousands of repetitions. When you’re in feedback mode, you’re strengthening reactive pathways, your brain gets better at correcting errors quickly. But when you transition to feedforward mode, you’re building a predictive model that can generate accurate movements without needing to see the result first.

Despite being an NBA player, having access to elite coaching and unlimited practice time, Mitchell Robinson has likely shot free throws in feedback mode for his entire career. His percentage from the line isn’t just bad luck, it’s a symptom of a brain that hasn’t built the internal model necessary for consistent shooting. Every trip to the line is still a reactive experiment rather than an automated execution. This doesn’t just apply to Robinson, but in many other cases with shooting.

The question is: why? What’s happening, or not happening in Robinson’s motor system that prevents this transition? To understand that, we need to dive into the neuroscience of motor learning and a framework called optimal control theory.

The Math Behind the Motion

Now let’s get into the science that explains why some brains build that internal model and others don’t.

In the early 2000s, neuroscientist Emanuel Todorov proposed a framework that revolutionized how we understand motor learning.3 He argued that the brain isn’t just trying to “get better” at movements, it’s actively solving an optimization problem. Specifically, it’s trying to minimize what’s called a cost function: a mathematical way of balancing two competing demands.

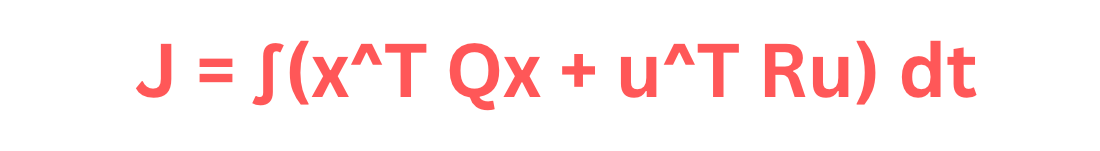

Here’s the equation for skilled movement:

It looks intimidating. But stick with me, because this equation explains everything about why Mitchell Robinson can’t shoot free throws.

Let’s break down what each piece means:

J = total “cost” the brain is trying to minimize. Think of it like a golf score, lower is better.

x = error, how far your movement deviates from the perfect trajectory. For a free throw, this is the difference between where the ball actually goes, and the center of the hoop.

Q = weight the brain assigns to accuracy. High Q means “I really care about being precise, even if it takes more effort.”

u = control effort, how much energy and muscle activation you’re using. Big, forceful movements have high u values.

R = weight assigned to efficiency. High R means “I want to minimize wasted energy, even if I’m less accurate.”

The integral symbol ( ∫ ) means this calculation happens continuously throughout the entire shooting motion, from the moment you start your dip to the moment the ball leaves your hand.

So what the equation is really saying is:

“Over the entire shooting motion, find the movement pattern that minimizes both how far off-target you are (weighted by Q) and how much unnecessary effort you use (weighted by R).”

Why Balance Matters

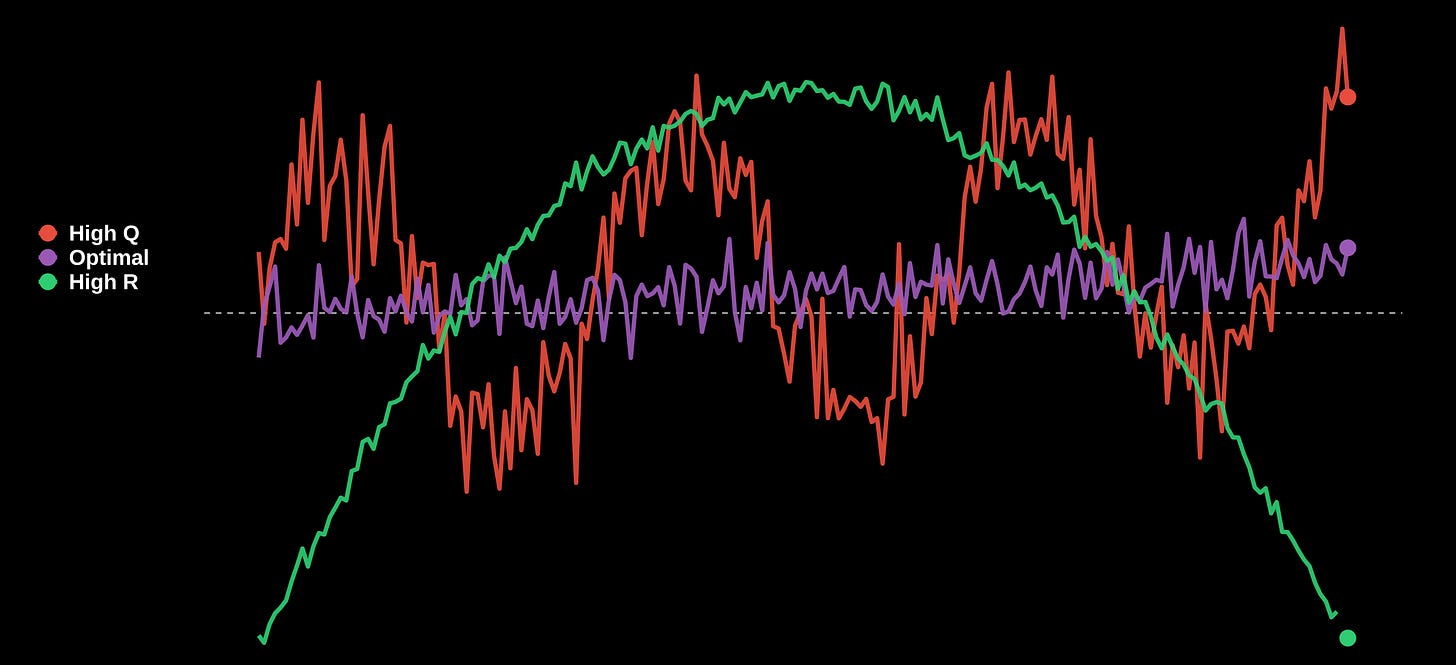

This framework explains why you can’t just “try harder” to get better at shooting. The brain is constantly negotiating a tradeoff between accuracy and effort, and getting that balance wrong creates predictable problems. Look at the three trajectories in the diagram:

High Q (red line): When the brain over-prioritizes accuracy, you get tense movements. The shooter is making constant micro-adjustments, trying to control every millisecond of the motion. This is the player who looks stiff at the line, overthinking every detail. The result? More variability, because all those corrections introduce noise. Markelle Fultz had a herky-jerky free throw form early in his career.

High R (green line): When the brain over-prioritizes efficiency, you get loose movements. The motion is smooth, but deviates wildly after because there’s not enough control. This is the player with “bad mechanics” and a form that looks effortless, but with an inconsistent release point. Think of a wild baseball pitcher, or Joakim Noah, who had a smooth transition into his motion, but the release point varied. Noah’s shot does not use much of his body, rather A LOT of arms and hands, therefore we can infer that his motion prioritizes efficiency.

Optimal (purple line): The Goldilocks zone. The movement is smooth but controlled, efficient and accurate. The brain has learned exactly how much effort is needed to hit the target consistently. Dirk Nowitzki had unorthodox shooting mechanics, but he kept his movements smooth, under control, and consistent.

The Feedforward Revolution

As I’ve stated, early in learning the brain is stuck in the feedback mode, it can only adjust Q and R values based on the results of previous shots. You shoot, you miss, and your brain says you need higher Q (more accuracy focus) or needs lower R (more control effort). As you get more skilled, your brain builds that internal model making a simulation of the entire shooting motion. Now, instead of waiting for feedback, your motor cortex can predict the outcome before you even shoot.

With feedforward control, the brain pre-computes the optimal balance of accuracy and effort. 4The basal ganglia, a brain region involved in habit formation, packages the entire shooting sequence into what researchers call “motor chunks”: action units that can be executed as a single command.5 You’re no longer consciously thinking “bend knees, align elbow, snap wrist”, your brain just runs the program labeled “free throw,” and the body executes it automatically.

Since I code, I think of it like writing and installing an R package. Once the package is installed (the motor chunk is formed), you just load the library with one command: library(freethrow). You don't reinstall the package every time; you just call the function. Elite shooters have a perfectly compiled package that executes identically every time.

This is why elite shooters describe being in rhythm or not thinking (They’re literally not thinking). The feedforward controller has taken over, and conscious interference (thinking) actually makes things worse.

What research suggests: Mitchell Robinson’s motor system has not successfully transitioned from feedback to feedforward control at the free throw line.

The Practice Problem

The answer isn’t about how much Robinson practices. It’s about how he practices, and more importantly, what conditions are necessary for the brain to transition from feedback to feedforward control.

Not all repetitions are created equal. In fact, research on motor learning shows that certain types of practicing can actually inhibit the development of more stable internal models. To understand Robinson’s struggles through this lens, we need to understand the difference between practice that builds motor chunks and practice that doesn’t.

Blocked Practice vs. Variable Practice

There are two fundamental approaches to motor skill training:

Blocked practice involves repeating the exact same movement over and over in succession, taking one-hundred free throws in a row in an empty gym, for example. This feels productive. You get immediate feedback, you can make quick adjustments, and your percentage often improves within the practice session itself. Variable practice involves mixing up the context, shooting from different spots, with different types of pressure, at different times in a workout. This feels less efficient. Your percentage might be lower during practice.

The finding: blocked practice produces better performance during the practice session, but variable practice produces better learning that transfers to new situations.6

Why? Because blocked practice keeps you in feedback mode. When you shoot a lot of free throws in a row, each shot is heavily influenced by the previous one. You’re constantly making micro-adjustments based on immediate results. Your brain is doing real-time error correction, not building a predictive model. Variable practice, by contrast, forces your brain to rely on the internal model because the context keeps changing. You can’t just adjust based on the last shot you need a stable motor program that works across different situations. This is harder in the short term, but produces more learning in the long term.7

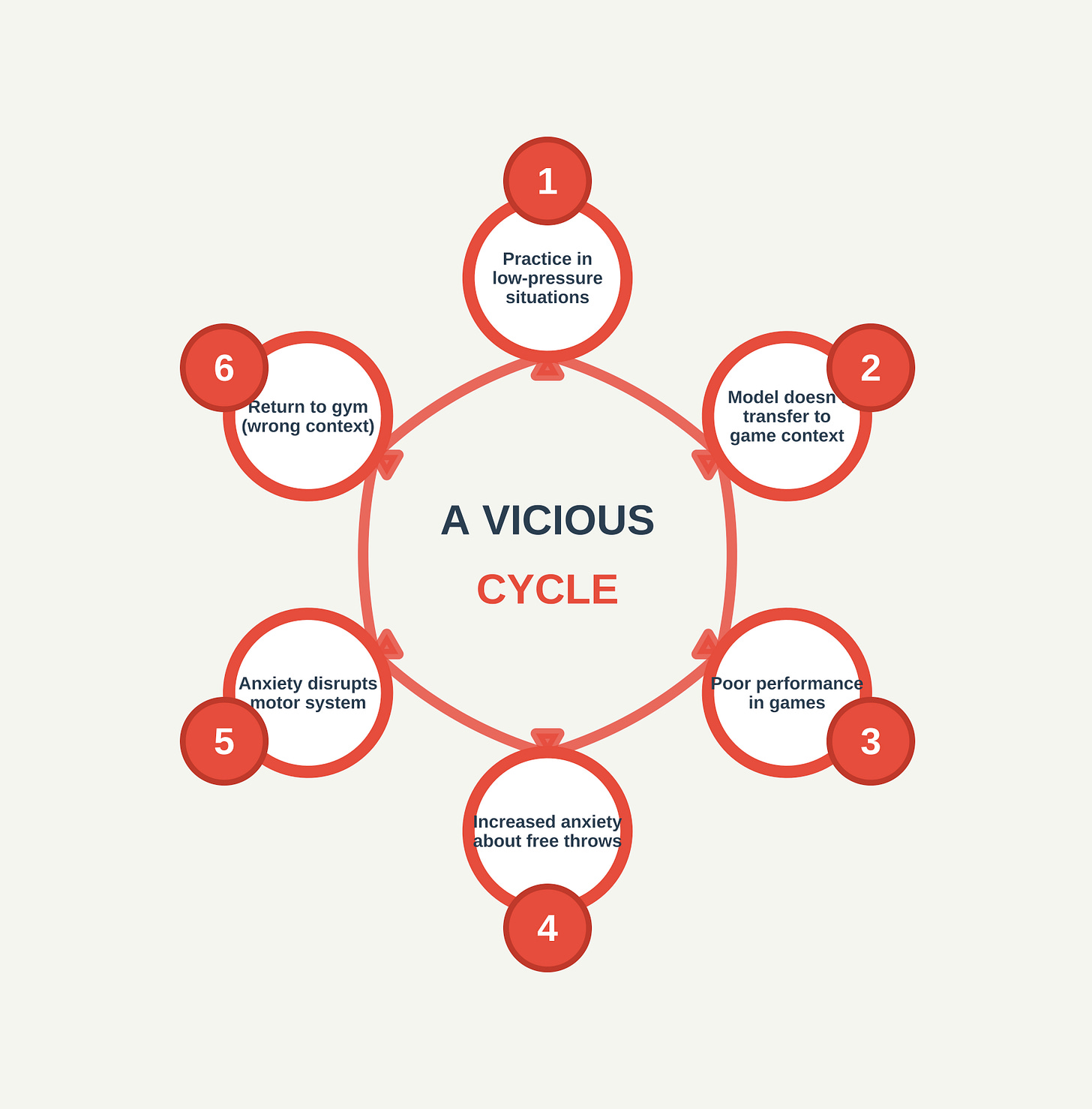

The Problem with Game Context

Here’s where Robinson’s situation can get even more challenging. When does he and other players shoot free throws in games? Usually after physical contact, often tired, maybe in high-leverage situations, maybe with a large crowd watching. And if you’re Robinson, intentional fouling, especially early in the game, introduces an added layer of abnormality that can further stress his shooting routine.

Internal models are context-dependent.8 If all your meaningful repetitions (the ones your brain treats as important) occur in a state of fatigue, pressure, and heightened arousal, your brain builds a model calibrated to those conditions. In turn when you practice free throws in a calm, empty gym, you’re essentially practicing a different skill.

For elite free throw shooters like Steph Curry or Steve Nash, this may not be a problem because their internal model is so robust it can generalize across contexts. But for someone like Robinson who likely hasn’t built a stable model yet, the context mismatch can be crippling.

Feedback Timing

We briefly discussed this: delayed feedback.

When a player shoots a free throw in-game, the feedback is immediate and binary: make or miss. But that feedback doesn’t say what went wrong mechanically. Was it the release angle? The release point? The arc? The follow-through? The brain gets outcome information (miss) but not process information (why).

Optimal motor learning requires immediate, specific feedback about the movement itself, not just the outcome.9 Elite shooters develop this through feel they know instantly when a shot “felt wrong” even before it hits the rim.10

My Plan Based on Findings

If we understand motor learning through an optimal control framework, this would be my personal prescription for a shooter on the level of Robinson:

Variable practice that matches game context: Robinson would likely benefit from practicing free throws in a fatigued state, after physical contact, with simulated pressure.

Curry's approach displays the proven model: he practices shooting in full-court settings with game-like movement patterns, rarely shooting with a full energy tank. While this isn't free throw specific, the principle directly applies. The internal model must be built under conditions that match game demands.

Immediate, specific feedback: Use technology (motion capture, shot tracking) to give Robinson instant feedback about release point, release angle, and arc, not just makes and misses. His brain needs to learn which motor commands produce which outcomes.

Consistent pre-shot routine: Build invariant elements into the approach to stabilize the internal model. If every free throw starts differently (different number of dribbles, different timing), the brain can’t build consistent predictions as easily. Jason Kidd had a unique one, and along with other changes, went from averaging 72% from the line in his first five seasons, to 81%(!!) for the rest of his career.

Blocked practice first, variable practice later: Some blocked practice is useful for discovering the general solution space. But it should transition to variable practice. Rudy Gobert offers the example of the variable practice principle. He'll never attempt these shots in NBA games, but by varying the context (distance and angle), his brain can learn underlying principles like arc, release, and follow-through rather than memorizing one specific motor pattern.

Mental rehearsal: Robinson can visualize successful free throws, with full imagery of the movement. This activates similar neural circuits to actual practice and can help connect the internal model with physical repetitions. Mental practice fires many of the same neurons as physical practice.

Final Takeaways: Robinson’s Progress

Based on my research, Mitchell Robinson doesn't need to shoot more free throws, he needs to shoot them under conditions that build a more stable internal model. For him, the goal isn't elite performance; it's crossing the line where opponents can’t exploit his weakness.

There's reason for cautious optimism. Robinson has been working with newly hired shooting coach Peter Patton. They've aimed to make mechanical adjustments, notably leading with his right foot instead of having his feet parallel, his elbow also stays in slightly longer as he begins his shooting motion.

Looking through the neuroscience lens, going from a parallel stance (both feet even) to right-foot-forward can help Robinson in a couple ways:

More consistent motor pattern and better stability - easier for the brain to build a stable internal model when things are the same every time. Instead of searching for an always parallel stance, Robinson has some room to maneuver his base. This extends to his body, as the right foot in front naturally squares his shoulders and keeps his elbow in longer.11

Reduced "cost function" - a sound, common mechanical change can aim to lower the effort (R) needed for the same accuracy (Q), lowering the cost function.

Robinson went 7-for-8 at the free throw line with this new change, a career-high for makes in a single game. But one good game doesn't mean things have changed. The real test will be sustainability: Can Robinson maintain this improvement over weeks and months?

This analysis applies established motor control theory to Robinson's public performance data and video. While I haven't measured Robinson's neural activity or observed his practice routines directly, the patterns in his shooting statistics and mechanics are consistent with what motor learning research predicts for athletes stuck in feedback mode. The recommendations I offer are grounded in peer-reviewed research, though their specific application to Robinson would require individualized assessment.

Todorov, E., & Jordan, M. I. (2002). Optimal feedback control as a theory of motor coordination. Nature Neuroscience, 5(11), 1226-1235.

Wolpert, D. M., & Flanagan, J. R. (2001). Motor prediction. Current Biology, 11(18), R729-R732.

Todorov, E., & Jordan, M. I. (2002). Optimal feedback control as a theory of motor coordination. Nature Neuroscience, 5(11), 1226-1235; Scott, S. H. (2004). Optimal feedback control and the neural basis of volitional motor control. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 5(7), 532-546.

Wolpert, D. M., & Flanagan, J. R. (2001). Motor prediction. Current Biology, 11(18), R729-R732.

Graybiel, A. M. (1998). The basal ganglia and chunking of action repertoires. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 70(1-2), 119-136.

Shea, J. B., & Morgan, R. L. (1979). Contextual interference effects on the acquisition, retention, and transfer of a motor skill. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 5(2), 179-187.

Schmidt, R. A., & Lee, T. D. (2011). Motor control and learning: A behavioral emphasis (5th ed.). Human Kinetics; Lee, T. D., & Magill, R. A. (1983). The locus of contextual interference in motor-skill acquisition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 9(4), 730-746.

Schmidt, R. A., & Lee, T. D. (2011). Motor control and learning: A behavioral emphasis (5th ed.). Human Kinetics. [Chapter on specificity of practice and context-dependent learning]

Schmidt, R. A., & Lee, T. D. (2011). Motor control and learning: A behavioral emphasis (5th ed.). Human Kinetics. [Chapter on feedback timing and knowledge of performance vs. knowledge of results]

Masters, R. S. W. (1992). Knowledge, knerves and know-how: The role of explicit versus implicit knowledge in the breakdown of a complex motor skill under pressure. British Journal of Psychology, 83(3), 343-358. [Discusses how elite performers develop implicit feel/awareness]

Human Kinetics shooting mechanics reference on shot line alignment 13. Cabarkapa et al. (2023). Biomechanical characteristics of proficient free-throw shooters—markerless motion capture analysis. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living.

This is fantastic, thanks, Shax. I’m going to read this a few more times to make sure I fully understand it.